When Manchester City announced that their commercial agreement with existing shirt sponsor Etihad Airways was to be expanded into a 10-year deal worth up to £400 million, the reaction of most observers in the football world was one of disbelief. This hugely lucrative contract includes the renaming of the City of Manchester Stadium in a naming rights deal that is likely to be the highest ever signed in football.

Indeed, Garry Cook, City’s ebullient chief executive, described it as “one of the most important arrangements in the history of world football”, while the CEO of Etihad Airways, James Hogan, was even more effusive, employing the full range of business buzzwords, “This is a game changing partnership agreement that redefines the traditional sports sponsorship paradigm.”

Of course, many people immediately assumed that one of the principal drivers of this deal was City’s need to boost their revenue in order to cope with the imminent arrival of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations that compel clubs to live within their means (if they wish to compete in Europe). This was tacitly confirmed by Cook, when he admitted, “The backdrop, of course, is UEFA’s Financial Fair Play and this deal helps (us) to continue to make significant progress in that area.”

Exactly how much is impossible for external analysts to say, as City have yet to publish the financial aspects of the deal. Initially, most newspapers suggested that it was worth £100-150 million, but now seem to have settled on £300 million, rising to £400 million. The truth is that nobody outside the club really seems to know for sure. Indeed, City released a statement to this effect, “The financial details of the comprehensive agreement announced last week between Manchester City and Etihad Airways remain confidential and figures being speculated about are not accurate.”

"Cooking up a good story"

The lack of certainty over the value of the sponsorship has not prevented prominent figures at other clubs from criticising the deal. The first to express his doubts was Arsenal manager, Arsène Wenger, who has often lambasted the practice of “financial doping” in the past, “It raises a real question about the credibility of the financial fair play. That is what this is all about. They give us the message that they can get around it by doing what they want.”

Liverpool’s new owner, John W. Henry, quickly followed suit, when he claimed that “Mr. Wenger says boldly what everyone thinks.” The Reds’ managing director Ian Ayre was unsurprisingly of the same opinion, questioning the transparency of the arrangement, given the close relationship between the sponsors and City’s owner, “The guys from UEFA said there would be a robust and proper process about related pay transactions.”

Wenger agreed, “It looks to me that Platini is very strongly determined on this. He is not stupid. He knows that some clubs will try to get around that and I believe they are studying behind closed doors, how they can really strongly check it.”

Certainly, UEFA talked tough last year, when Andrea Traverso, their head of club licensing and financial fair play, described what would happen if clubs attempted to beat the system by taking advantage of loopholes, “Should the clubs put in place specific structures that allow them, in ways we didn't think about, to easily get around some of the principles, we could amend these rules to catch up with these situations.”

"Michel Platini: this is how FFP will work"

UEFA President, Michel Platini, ostensibly substantiated the concerns of City supporters that he was targeting their club when he specifically mentioned them last year during the announcement of the new financial measures, “Manchester City can spend £300 million if they want to, but if they are not breaking-even in three years, they cannot play in European competition.”

However, Garry Cook did not appear overly concerned, “We have a very open dialogue with UEFA. We have had several meetings with them and they are very supportive of our plans.”

Indeed, UEFA’s response to City’s mega deal was far more measured than a year ago, “We are aware of the situation and our experts will make assessments of fair value of any sponsorship deals using benchmarks.” So, City are no longer being singled out, at least publicly, with UEFA keen to stress that they will investigate all major sponsorships whatever the club, which “will then be considered by the Club Financial Control Panel, together with any relevant information the clubs present regarding the deals, when they assess the break-even requirements.”

So how will UEFA assess City’s deal?

This is effectively a three-stage process. First, they have to decide whether the deal is a “related party transaction”. If they believe that it is, then they have to estimate the “fair value” of the deal. Finally, if the actual value is higher than the fair value, the difference is deducted from the revenue included in the FFP break-even calculation.

"Every cloud has a Silva lining"

The notion of related party transactions is evidently important to UEFA, as no fewer than three pages of the FFP regulations are dedicated to defining exactly who or what is a related party. The key point here is that “close members of the family” are considered to be related parties, so long as they have “control” or “significant influence” over the club.

In this case, Etihad Airways is owned by the government of Abu Dhabi, whose ruler Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan is the half-brother of City’s owner Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan. It is conceivable that City might be able to demonstrate that no influence exists, but it would appear that there is a prima facie case to answer.

It is not clear whether the fact that the majority of City’s commercial sponsorships come from the Gulf state, including the Abu Dhabi Tourist Authority, Etisalat and Aabar Investments, will have any bearing on UEFA’s ruling, but Cook himself has admitted that it is “clearly evident” that there is a strong Abu Dhabi bias. Anyway, for the purpose of our analysis, let us assume that UEFA do indeed treat this deal as a related party transaction.

In fact, the FFP regulations expressly include “sale of sponsorship rights by a club to a related party” as their first example of “transactions that require a licensee to demonstrate the estimated fair value.” This has also been verbally confirmed by UEFA’s general secretary, Gianni Infantino, who said that such transactions would be compared to similar deals already in place.

"Fast Kompany"

Again, John W. Henry expressed his scepticism, when he asked, “How much was the losing bid?” Wenger also cast doubts on the value of the deal, “If FFP is to have a chance, the sponsorship has to be at the market price. It cannot be doubled, tripled or quadrupled, because that means it is better we don’t do it and leave everybody free.”

However, Garry Cook argued, “There’s real value in that partnership. Financial Fair Play isn’t the driver, commercial growth is the driver.” That obviously makes sense for City, but how about Etihad? The airline’s executives would contend that this deal has already been superb for their profile, as evidenced by last week’s intense media exposure, and will provide them with a more than acceptable return on their investment.

Not only do City compete at the upper levels of the most viewed league in the world, but their global visibility has been dramatically enhanced by their qualification for the Champions League. Indeed, it is quite possible that the airline gets more bang for its buck with City compared to more established clubs, as the exposure is higher with such a project. Big money deals may be old hat at clubs like Manchester United or Real Madrid, but it’s a relatively new phenomenon at Eastlands, sorry, the Etihad Stadium.

"Nigel de Jong - Dutch courage"

Some have questioned how it could make sense for a loss-making company like Etihad Airways to splash out such a large sum in sponsorships, but that ignores the fact that this investment is all about “building the brand” in the same way as Emirates have done in the past.

At this stage, it’s worth pointing out that the FFP regulations refer to “fair value”, as opposed to the “market value” that is incorrectly used by much of the media. The difference can be seen by an analogy in the housing market. If you decide to sell your house and 99 people offer you £250,000, that would be considered fair value, but if one enormously wealthy individual likes it so much that he bids £500,000, that is the market value.

This is an important distinction, as market value would be easy to prove. Sports lawyer Andrew Nixon of Thomas Eggar LLP asserted, “Competition law challenges rarely succeed on sponsorship deals. There is a vast number of football teams and leagues airlines can sponsor and there are many viable market alternatives.”

Importantly, even if UEFA rules that City’s deal is above fair value, it is only the excess that would be deducted from the club’s income for the purposes of the FFP break-even calculation and not the entire agreement. In other words, if the deal is worth £30 million a year and UEFA consider the fair value to be £25 million, only £5 million would be deducted.

"Don't cry for me, Argentina"

UEFA’s difficulties in assessing the fair value of the deal are compounded by the structure of the deal, which covers far more than the stadium naming rights that were initially reported. This is just one element of a broad agreement that also includes an upgrade of the current shirt sponsorship and naming rights for the Etihad Campus, which encompasses a large part of the Sportcity site in East Manchester.

Furthermore, given the long-term nature of the contract, City could argue that they have built in uplifts, as the sponsorship market might be even more lucrative in ten years time. In addition, part of the money is almost certainly based on performance bonuses, e.g. qualifying for the Champions League or winning the Premier League, which might make it more palatable to the powers that be.

As I said earlier, nobody can honestly claim to know the actual revenue split of the deal, but we can make a reasonable working assumption that the shirt sponsorship is worth £20 million a year, the stadium naming rights £10 million and the campus another £10 million. As we assess each element for fair value, it will become clear why these values have been chosen.

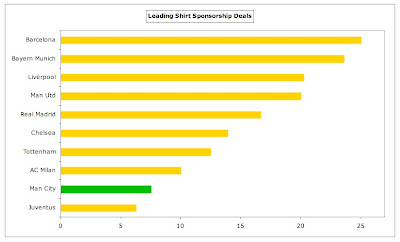

An assumed shirt sponsorship value of £20 million would place City right at the top of English deals, generating the same annual revenue as Liverpool and Manchester United. Those clubs might argue that City’s historical performance should not allow them to be at the same level, but the counter-argument would be that nobody complained about Liverpool increasing their sponsorship deal by £12.5 million a season when they replaced Carlsberg with Standard Chartered last season, even though they had not qualified for the Champions League. Similarly, Tottenham managed to increase their sponsorship by nearly 50% from £8.5 million to £12.5 million (via an innovative combination of Autonomy and Investec), based on just one season in the Champions League.

If the net is cast a little wider, Bayern Munich’s sponsorship deal with Deutsche Telekom is worth around £23 million, though performance bonuses could take that above £25 million. That might seem reasonable for a club with Bayern’s tremendous record, but the value of deals at other German clubs is more debatable, particularly Schalke’s money-spinning deal with Gazprom.

Equally, the announcement of Barcelona’s first ever shirt sponsorship deal with the Qatar Foundation, a non-profit organisation, did not attract the same levels of opprobrium as City’s. This has been widely reported as €150 million over five years, but is actually worth up to €170m, as it also includes €5 million trophy bonuses and €15 million for “the concept of commercial rights”. So, it is likely to be worth €34 million a year (or just under £30 million at the current exchange rate).

"The Italian Job"

Others have pointed disapprovingly at the magnitude of the increase in City’s shirt sponsorship, but they have cited a current value of £2.3 million for the Etihad deal, which looks far too low. Deloitte and other reputable sources have said that this deal is worth £25 million over three seasons, so with uplifts, it’s around £7.5 million as we speak. Other commentators have probably confused this with City’s previous deal with Thomas Cook that was worth £2.3 million.

If UEFA genuinely want to investigate the value that companies obtain from sponsorship, it might be pertinent to ask why they don’t also take a look at Emirates, which sponsors many different clubs. Or indeed the ethicality of clubs being sponsored by gambling sites, which is a growing trend in football marketing.

Probably the most contentious aspect of the deal is the stadium naming rights, which is virtually unprecedented in football at its estimated value. There are very few decent benchmarks in the Premier League with the obvious comparative being Arsenal’s deal with Emirates, which was worth £90 million (£100 million less £10 million fees), covering 15 years of stadium naming rights (£42 million) and 8 years of shirt sponsorship (£48 million).

This works out to just £2.8 million a year for the naming rights, which is considerably lower than City’s deal, but it’s not really a fair comparison for many reasons. Not only have sponsorship values in general grown significantly since the agreement was signed, but also this particular deal is very much a special case, as Arsenal compromised on the total value so that the cash payments would be heavily front-loaded to help finance the construction of the stadium. When questioning the merits of City’s deal, Arsène Wenger drily observed, “We must have done a bad deal”, but there’s more than a grain of truth in that assertion with Emirates admitting that they “did well with Arsenal.”

"Get your Yaya's out"

It’s worthwhile looking at Germany for a more considered view on naming rights, as the market there is more than four times as large as in England, according to Sport + Markt’s 2011 Naming Rights report. Many clubs in the Bundesliga have sponsorship deals for their stadiums, including Borussia Dortmund (Signal Iduna), Hamburg (Imtech), Wolfsburg (Volkswagen), Stuttgart (Mercedes-Benz) and Eintracht Frankfurt (Commerzbank).

However, perhaps the best known is Bayern Munich, whose deal with Allianz is worth €90 million over 15 years, producing €6 million (£5 million) a year. On the face of it, this might suggest that City’s £10 million deal is over-valued at double the money, but this is far closer than the difference in overseas TV rights, which are around 14 times higher in the Premier League than the Bundesliga. Obviously, this is not quite the same thing, but it’s food for thought.

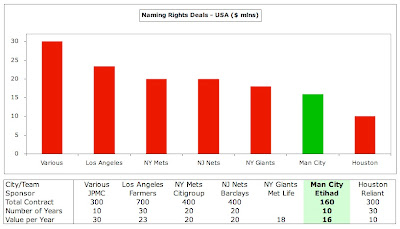

Or UEFA might look even further afield to America, where naming rights are a well-established feature of the sporting landscape. Virtually every major sports arena is now named after a sponsor that provides the club with a healthy source of income. The concept is nothing new under the sun either, as Times Square was named after the New York Times way back in 1903.

Although the link between football and American sports like baseball, NFL and NBA may seem rather tenuous, fundamentally the principle is identical and it seems quite pertinent with the influx of foreign owners into English football. Some of the stadium deals signed on the other side of the pond provide an indication of where this market may go in the future, going as high as $30 million a year paid by JP Morgan Chase for Madison Square Garden. Citigroup and Barclays both pay $20 million a season, the former to the New York Mets, the latter to the New Jersey Nets. Farmers Insurance have paid an astonishing $700 million over 30 years to name a stadium in Los Angeles where a team is not even established yet.

This does rather beg the question of how the sponsor benefits from such a deal: what’s in a name? The obvious answer is brand awareness with a raised profile, which is particularly well served if it is a new stadium. This point was seized upon by Ian Ayre, Liverpool’s managing director, who noted, “It hasn’t happened in Europe that a football club has renamed an existing stadium and it’s had real value.” This is correct, but it’s doubtful whether too many fans are attached to the name Eastlands (or even the City of Manchester Stadium). It would be a different story if this had been Maine Road. This is why it would be difficult to sell naming rights for grounds like Anfield or Old Trafford, as whatever name anybody tried to call the stadium, everyone would still use the old/real one.

One valid point about City’s agreement is that other Premier League clubs have to date been unsuccessful in securing large naming rights deals, though paradoxically this announcement could potentially help others make progress in their discussions. Chelsea have been looking to secure a partner for some time with analysts suggesting that £10 million is the objective, while Liverpool would be equally eager if they move to a new stadium, as Ayre confirmed, “We already have a very healthy dialogue in place with several leading brands regarding naming rights.”

"Hart and Soul"

That said, the Sports + Markt report confirmed that the value of stadium naming rights has been steadily rising, up over 60% from €48 million in 2007 to €78 million in 2010 with the total projected to increase to €87 million in 2011.

Given the difficulties inherent in finding solid comparatives for naming rights, it is possible that UEFA might look at this as just another commercial deal. If they did so, they could not help noticing that the bar is being constantly raised in the commercial sphere, e.g. contracts with kit suppliers. Liverpool’s recent £25 million deal with Warrior Sports is more than double the amount that they previously received from Adidas, helped by the relationship that the new owners enjoyed with the company, which already provides kit for the Boston Red Sox.

Similarly, Manchester United are in discussions to extend their deal with Nike for a record £450 million, which would be worth around £35 million a year, a £10 million increase. If you think that’s impressive, the French national team’s deal with Nike is worth €320 million over 7½ years, which works out to about £37 million a year for just a handful of matches.

In short, commercial opportunities in football are big business these days and City’s deal should be assessed in that light. In a strange way, it brings to mind the movie “The Wizard of Oz” and the famous line about not being “in Kansas anymore.”

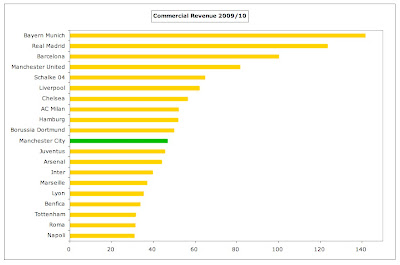

With the exception of Manchester United (£81 million), English clubs have lagged their continental counterparts when it comes to making money from commercial opportunities, growing fatter on a diet of ever-increasing TV contracts. Not only do the Spanish giants, Real Madrid and Barcelona, earn substantially more at £124 million and £100 million respectively, but German clubs also consistently generate more income. This description does not just refer to Bayern Munich, who earn an astonishing £142 million commercial revenue a year, but also clubs like Schalke, Hamburg and Dortmund.

There’s certainly room for improvement, which is exactly what English clubs are belatedly doing. In 2010/11, Manchester United’s commercial revenue will exceed £100 million, while Liverpool’s £62 million will ultimately be boosted by £25 million growth from the Standard Chartered and Warrior deals. Likewise, Chelsea will increase their revenue by £12 million from £56 million following better deals with Adidas and Samsung.

In other words, it’s become a commercial arms race with each of the leading clubs significantly increasing their commercial revenue in their own way – and City are no exception.

Actually, I tell a lie, as City’s deal includes one unique element, the Etihad Campus, which is perhaps the cleverest and certainly the most innovative part of the agreement. This is a gigantic redevelopment project on 80 acres of land adjacent to the stadium, including a relocated training ground, youth academy, a sports science facility, office space, a call centre and City Square retail outlets. The academy will be seriously impressive, catering for up to 400 young players, with 16 football pitches, a 7,000 capacity stadium for youth matches and on-site accommodation.

"Opportunities (Let's Make Lots of Money)"

Such a development will not only benefit the community, but will bring a raft of sponsorship opportunities. Nothing like this has been done before, so it will be very difficult for UEFA to assess and almost impossible to deem unfair. In fact, this is exactly the type of expenditure that UEFA is trying to encourage with direct youth and community development costs being totally excluded from the FFP break-even calculation. For someone with pockets as deep as Sheikh Mansour, this is effectively “free” money, at least in terms of FFP.

On top of that, Annex X allows any profits from non-football operations to be included in the calculation, so long as the operations are: (a) based at, or in close proximity to, a club’s stadium and training facilities, such as a hotel, restaurant, conference centre, business premises (for rental), health-care centre, other sports teams; and (b) clearly using the name/brand of a club as part of their operations.

That sounds very familiar, so it’s a double whammy for City: the costs for this development are excluded, while the profits from the business located there are included. Not only that, but UEFA should be positively delighted, as it’s very much in the spirit of the stated objectives of FFP. Given those factors, the temptation must be to load up the sponsorship on this part of the agreement, so the deal split might be more like £10 million on shirt sponsorship, £5 million on naming rights and £25 million on the campus. We shall see.

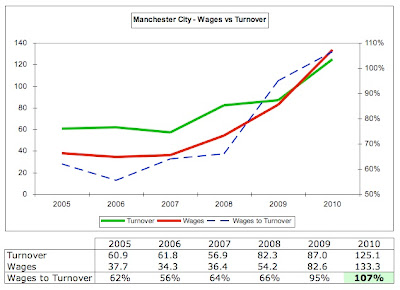

Even with the benefit of this deal, City are still a long way from break-even, having recorded a thumping great loss of £121 million in 2009/10. The deficit is anticipated to be even higher last season, as the impact of the previous summer’s incoming players will have further increased the wage bill and amortisation. Nevertheless, City insist that matters will improve. Garry Cook stated, “Clearly our intention is to comply. FFP is on our conscience. We talk about it at every board meeting and it’s part of our long-term plan.”

Even the spendthrift manager Roberto Mancini now appears to have accepted the new financial realities, “FFP is for everyone”, saying that City would no longer “pay £10 million more than other clubs” for new players. Indeed, so far this summer, City have only signed Gael Clichy from Arsenal for £7 million and Montenegro defender Stefan Savic for a similar amount. That’s chicken feed by the Blues’ recent standards, though there’s still time for them to splash out on another big name.

That said, City are very keen to reduce their bloated wage bill by offloading players that no longer fit into Mancini’s plans, including the likes of Emmanuel Adebayor, Craig Bellamy, Wayne Bridge and Shay Given. From this season, the club’s revenue will also be significantly boosted by a Champions League campaign and, of course, the vast growth in sponsorship deals.

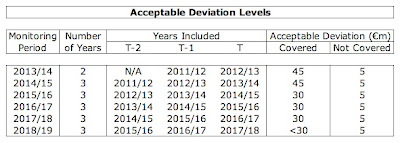

They will also be helped by the UEFA’s so-called “acceptable deviations”, namely the €45 million aggregate losses allowed in the first two-year monitoring period, which means that they don’t have to actually reach break-even from day one, so long as the owner covers the losses, which I think we can safely assume.

If that wasn’t enough, the glide path is made even easier by clubs being allowed to exclude wages from players signed before June 2010, so long as they are reporting an improving trend in their accounts. Granted, that “loophole” only exists for the first two monitoring periods (2013/14 and 2014/15), but it will buy City time to execute their strategic plan.

In essence, that has been to spend big in the short-term on transfers and wages in order to break into the Premier League top four, so that they can qualify for the riches of the Champions League, which is easily worth £30 million additional revenue a season. That extra income will contribute towards balancing the books while the academy can be established, producing top class players in-house, but the growth in commercial revenue is still a vital component to that strategy.

One of UEFA’s main objectives in implementing FFP was to “curb the excessive spending and inflated transfer fees and player salaries that have endangered football in recent years.” To a certain extent, there are some signs that this is happening, but new regulations often have unintended consequences and it appears that clubs are also striving to increase their revenue, as opposed to simply cutting costs.

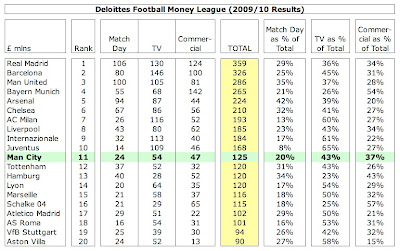

Even though City’s revenue grew by an impressive 44% in 2009/10 to £125 million, which pushed them up to 11th place in the Deloitte Money League, this is still a long way behind other leading clubs. For example, it’s less than half of local rivals Manchester United (£286 million) and £100 million lower than Arsenal (£224 million). On the continent, both Real Madrid (£359 million) and Barcelona (£326 million) generate £200 million more than City every season.

City could look to increase their match day revenue, which they have partially addressed via a new agreement with the council, whereby the club pays them a fixed amount regardless of the attendance instead of the previous percentage. Any further growth would mean raising ticket prices, increasing the corporate seats or expanding the capacity of the stadium. The first two moves would be unpopular with fans, while the stadium expansion is longer-term in nature.

Plans exist to increase the capacity of the stadium from 47,000 to at least 60,000, but this would not be entirely straightforward, due to its awkward design. There have been some concerns that City would struggle to fill a larger stadium. Although their attendances have always been good (4th highest in the Premier League), they do not regularly achieve full capacity. That said, the crowds have risen since the move to Eastlands and continued success on the pitch should produce a further increase, as was the case with Chelsea after Abramovich’s arrival.

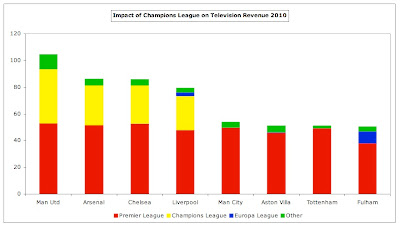

Television has been the big driver of revenue growth at football clubs and the latest Premier League deal for the three years between 2010/11 and 2012/13 helped increase City’s distribution from £50 million to £56 million. However, this is a tide that floats all boats with very little difference between the leading clubs. The real distinguishing factor is the honey pot known as the Champions League, so City’s qualification will have a transformational impact on their revenue, but it’s a one-step growth.

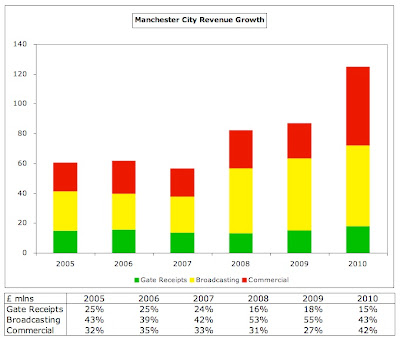

So, with match day and TV relatively fixed, it’s really down to the commercial side, notably sponsorships, to substantially close the gap with the big boys. Even before the blockbuster Etihad deal was announced, City’s revenue from commercial activities had more than doubled in 2009/10, including an increase of almost 400% in revenue from corporate partnerships up from £6.5 million to £32.4 million.

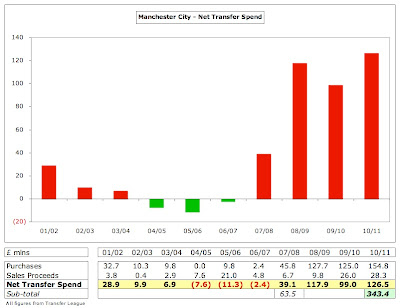

This explosive growth has inevitably raised suspicions, particularly given the provenance of the sponsors, but the criticism of City has taken on something of the nature of a moral crusade with many commentators accusing the nouveaux riches of buying success, after Sheikh Mansour ploughed close to a £1 billion into the club since acquiring them in 2008. There’s little doubt that City have contributed to the inflation in transfer fees and wages, with net transfer spend of £343 million in the last three seasons and a wages to turnover ratio of 107%, though they are hardly alone in that.

However, there are two sides to every story and there are a couple of facets of this deal that should be commended. From the point of view of the fan, it is surely better that a club tries to grow its revenue by taking more money from sponsors than raising ticket prices. This is where Arsenal’s criticisms ring a little hollow after they hiked ticket prices that were already among the highest by 6.5% for next season.

And while I yield to nobody in my admiration for Sir Bobby Charlton, his suggestion that big clubs should not think about renaming their stadium should also be considered alongside Manchester United’s stratospheric ticket price rises. Indeed, City were top of the ING Direct Value League last season, measured by comparing clubs’ season ticket costs with Premier League performance.

City’s commercial deal will also benefit the local community, which is why the council agreed to let City sell the naming rights of a stadium that is not owned by the club, but the council. In fairness, the club had already contributed £30 million to the stadium conversion costs after the Commonwealth Games, but the council’s willingness to let the deal proceed on these terms still came as a surprise to some.

However, the council will receive £20 million over the next five years, and, more importantly, their leader points to “the regeneration of the area, delivering significant community and economic benefits”, including the creation of new jobs. Faced by severe government cuts, the cash-strapped local authority have gratefully accepted City’s proposal for this deprived neighbourhood, describing it as “great news for Manchester, reinforcing our sporting, transport and economic growth.”

Of course, other clubs have also been very active in their community, but this plan is on an altogether different scale. Yes, it might feel a little like wealthy philanthropists establishing charities as a way of reducing their tax bill, but the fact is that the community will still gain.

This has not stopped other clubs from sniping, led by Bayern Munich chief executive Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, who also happens to be chairman of the European Club Association. When commenting on City’s large financial losses, “Kalle” sniffed, “Maybe they know a trick I don’t that will allow them to take part in the Champions League.” This is the same Bayern where two of their most prominent sponsors, Adidas and Audi, each own around 10% of the club.

Similarly, Wolfsburg is a wholly owned subsidiary of Volkswagen Group, who also pay for the club’s stadium naming rights and shirt sponsorship. Little wonder that Stefan Szymanski, professor of sports business at London’s Cass Business School, said, “If there’s a question of fair value in relation to an Abu Dhabi client sponsoring Manchester City, I see no reason why the same questions can’t be raised about corporate Germany sponsoring German football.”

"Gael force"

If UEFA did decide to broaden their investigations into other sharp practices, they could also take a look at the ridiculously unfair advantage enjoyed by Real Madrid and Barcelona with their huge slice of the Spanish TV pie. And while they’re about it, what about those clubs that directly inflate the transfer market by paying over the odds for average players (naming no names)?

My simple point here is that if you look hard enough, you will surely find reasons to investigate activities at numerous clubs, so it would be very harsh for UEFA to zoom in on City. There will be many such deals sailing close to the edge and there must be a better use of UEFA’s time than to review each one. Adopting a basic tenet of the English legal system, a reasonable man will know when a deal is completely ludicrous, e.g. a £200 million annual season ticket, but to my mind City’s deal does not fall into that category.

While UEFA’s credibility over FFP is at stake, there’s every indication that they will help clubs towards break-even, instead of throwing them out of Europe. Otherwise, in City’s case, it would feel like they should re-release The Clash’s seminal “Know Your Rights” with slightly modified lyrics: “You have the right to sponsors’ money, providing of course you don’t mind a little humiliation, investigation, and, if you cross your fingers, authorisation.”

"Sometimes a picture is worth a thousand words"

There may be a whiff of creative accounting around this incredible deal, but there’s also genuine substance and benefit to the community. City’s commercial growth might have been fuelled by money from companies that are at the very least “friendly” towards their owner, but when the deals are broken down the sums are not inordinately high, so are more or less in line with benchmarks.

Furthermore, the proceeds will be invested in a state-of-the-art academy with the objective of producing homegrown young players who will ultimately replace the imported “mercenaries”. It’s a well-considered plan that seems to me to be within both the letter and to a large extent the spirit of FFP.

0 comments:

Post a Comment